The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“Corporation: An ingenious device for obtaining profit without individual responsibility.”

– Ambrose Bierce

The first corporations weren’t like the corporations we know today. Initially created for only temporary purposes, such as the building of roads and aqueducts, the publicani, public contractors, lured individuals to invest in infrastructure for the public good while also making a profit. The word ‘corporation’ itself is derived from the Latin corpus, meaning body, in this case a body of people.

The first organizations to incorporate were governments, from the empire itself, populus Romanus, to cities throughout the region, political groups, trade guilds, and religious organizations. The oldest surviving corporation, the Benedictine Order of the Catholic Church, was established in 529 AD. Not built to last, but merely to fulfill a purpose, early Roman corporations were a far cry from the gods of capitalism they have become in more recent years.

Some early corporations grew to employ thousands of people, but the practice of corporations wouldn’t truly take hold until the Middle Ages. They would be refined further by the Age of Enlightenment and the Renaissance. And they were chiseled into their current incarnation with the Industrial and Information Revolutions.

As the organization of corporations developed, the Roman Catholic Church had some organizing of its own to do. Before its onset, early Christians did not fare well in Rome, but the persecution seemed to merely strengthen their resolve to believe. Although they were seemingly ecstatic about their new way of seeing the world, they refused to take part in the Roman festivals, they rejected the dizzying array of Roman gods, they were highly critical of other people’s traditions, and basically, they came across as huge buzz kills, as many of them still are today.

Unlike modern America, the majority of Roman leaders were not professed Christians, and the persecution early Christians felt was entirely different than some Christians complain about today. Where modern American Christians sometimes feel persecuted when they can’t put a nativity scene on the courthouse steps, when Emperor Decius ordered the persecution of Christians throughout the Roman Empire in 250 AD, the persecutions they faced were more along the lines of having their property seized, children abducted into slavery, and being fed to lions. Chances are good that they wouldn’t make too much of a stink about the nativity scene.

Nevertheless, when Gallienus became emperor ten years later, he issued an edict calling for Romans to show more tolerance to Christians, and some estimates state that by the year 300 AD, 10% of the Roman population was Christian. However, one of the problems with empires is their lack of consistency as leaders come and go, so when Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius were prevailing over the empire, they made up for the lost 40 years of Gallienus’ even hand, and they went right on back to rescinding Christians’ rights and making their lives a very close facsimile of the hell they were really trying to avoid in the afterlife. Although this Great Persecution was incredibly harsh, it was short-lived as Constantine I took the throne a few years later and took a shine to the new religion. Legend has it, he claimed Jesus came to him in a vision and told him to, “Conquer in my name.”

Although Christianity wouldn’t become the official religion of the Roman Empire until 380, under the rule of Theodosius, Constantine did quite a bit of the footwork in organizing the religion in such a way as to be more palatable to everyone involved. For instance in 336, he merged the Roman festival of Saturnalia, celebrating the birthday of the god Saturn, the birthday of the pagan sun god Mithra, the Jewish celebration of Hanukkah, and the Winter Solstice with the Jesus story to celebrate the first Christmas, inspiring Pope Julius I to declare December 25 as Jesus’ official birthday just a few years later. No one really knew when Jesus was actually born, but it offered up a nice diplomatic solution for everyone to celebrate together at the time.

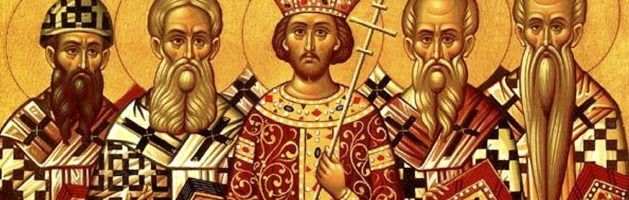

But establishing a more organized Christianity wasn’t just about the holidays. As Christianity grew throughout the persecutions and into its wide acceptance, a variety of sects emerged, and each of them had their own ideas on what the accepted scriptures meant, which ones were actually scripture, and exactly what they were supposed to believe to get the most out of this new religion. Since one of the biggest arguments was regarding Jesus’ divinity, which was a pretty big deal to Constantine, he called together a council of 1800 leaders from the various sects in order to develop some homogenized harmony.

![]() Only 300 or so were able to make it to this first Council of Nicea, and had there been a larger turnout, chances are that the process would have taken even longer. After several months of the first session and a few follow up sessions over the next few decades, the group of bishops were finally able to put together a list of beliefs that would become mandatory for anyone calling themselves a Christian. Anyone who didn’t profess to believe in the Nicene Creed was exiled.

Only 300 or so were able to make it to this first Council of Nicea, and had there been a larger turnout, chances are that the process would have taken even longer. After several months of the first session and a few follow up sessions over the next few decades, the group of bishops were finally able to put together a list of beliefs that would become mandatory for anyone calling themselves a Christian. Anyone who didn’t profess to believe in the Nicene Creed was exiled.

A big issue for the first council was coming to terms with what had come to be regarded as the Holy Trinity. Although most of the works they were regarding as scripture were nebulous about the idea, it had been written about by a number of 1st century Christian writers like Tertullian and Origen, and touched on again in the 2nd century by Ignatius, Polycarp, and Justin Martyr. But once they reached a point of consensus in 362, the Christian religion finally had a foundation they could build on.

However, once they had established the various points on the three aspects of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, there was still the issue of which of the many books that were in circulation would be actually considered holy scripture. There are not any records of this issue being discussed in the Council of Nicea, and unfortunately, not much of anywhere else either. Beyond the accepted Jewish scriptures, most of which would eventually become known as the Old Testament, early Christians weren’t exactly particular about which books should be heralded as the perfect, infallible declarations of God and which ones were just a really good read.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!