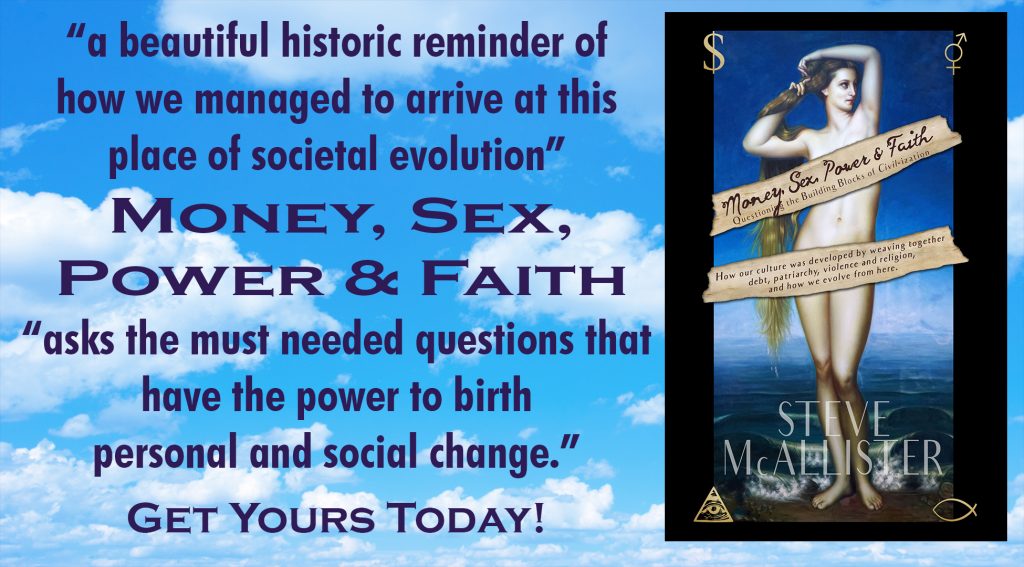

The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“There must be more equality established in society, or morality will never gain ground, and this virtuous equality will not rest firmly even when founded on a rock, if one half of mankind be chained to its bottom by fate, for they will be continually undermining it through ignorance or pride” – Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Although Americans’ high rates of gun deaths, suicide, and imprisonment may point to a nation of self-hatred, in other aspects of our culture, we are directly addressing how much we do still love ourselves and will no longer tolerate abuse. The term “sexual harassment” was first used in a 1973 report by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology called “Saturn’s Rings” about a variety of gender issues. It rose to prominence in 1975 when a former employee of Cornell University by the name of Carmita Wood, who resigned after being groped by her supervisor, was denied unemployment benefits on the grounds that she quit for “personal reasons”.

As Carmita worked with activists from the university, they gave women everywhere the opportunity to start telling their stories of sexual harassment. For most of America’s history, women merely endured sexual advances and mistreatment, and if they couldn’t, they simply quit their jobs. Yet as more women joined the workforce throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the stories of assaults, masturbatory displays, threats, and requests for sexual favors only increased. A 1976 survey in Redbook magazine called “How Do You Handle Sex on the Job?”, 92% of women in the workforce said sexual harassment at work was a problem, a majority of them calling it “a serious one.” Time magazine reported that “as many as 18 million American females were harassed sexually while at work in 1979 and 1980.”

A January 2018 online survey conducted by non-profit group Stop Street Harassment found that not only do 81% of women claim to have been sexually harassed in their lifetimes, but 43% of men do as well.

Sexual harassment gained an even greater limelight in 1991 when Anita Hill testified against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas about his inappropriate workplace comments regarding the size of his penis and his favorite porn star. Yet although shining a light on the sexual depravity of men in government did much to encourage other women to speak out about their experiences with sexual harassment, it wasn’t until Hollywood’s infamous “producer’s couch” was called out that the torch really started to burn. After actress Ashley Judd shared her story about the sexual advances she had endured from producer Harvey Weinstein with The New York Times, actress Alyssa Milano called for solidarity among women by launching the #metoo movement.

On October 15, 2017, Milano tweeted “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet,” based on a phrase coined by civil rights activist Tarana Burke in 2006. The aftermath of support shows that as a society, we want to move beyond the degradation we have experienced. Millions have since used #metoo in their social media updates. The movement has grown to include men who have come to regret times they have made women feel harassed, sharing their own tweets of responsibility like #ihave and #ididthat, and others have expressed their willingness to change and raise awareness by sharing #iwill. Where once women were afraid to speak out about sexual harassment, now men are reconsidering their behaviors.

Of course, sexual misconduct is nothing new in America.

In addition to being the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton also initiated one of the first recorded American sex scandals after having a year-long affair with a married woman and paying her husband over 1,300$ in blackmail money to keep quiet about it. Since then, stories of our public officials have been replete with tales of extramarital affairs, sex with slaves, homosexual relationships, mistresses, brothels, divorces and remarriages, strippers, prostitutes, illegitimate children, contributing to the delinquency of a minor, statutory rape, sodomy, oral sex, second families, sex with staffers, explicit emails, groping, tickling, fondling, lewd conduct, forcible kissing, assault, and rape. Sexual misconduct seems to be so much a part of our national fabric that over 200 years since our first scandal, the current president’s lawyer paid an adult film star 100 times the blackmail Hamilton did in order to keep her quiet about her alleged sexual escapades with the soon-to-be-commander-in-chief.

While women are finding the strength to speak about what has happened to them throughout the history of a culture reigned over by patriarchy, it would appear that the rising awareness is already starting to change the tide. Although sexual harassment has become more openly discussed over the last several years, data from the US Equal Opportunity Employment Commission reveals that there were 12,695 reported cases in 2010 and only 12,428 in 2017. Given the attention it has been given by both mainstream and social media, like violence, one would expect the numbers to be higher. Yet it seems that “enough” is more than just a slogan being shouted by the newly brazen, but an understanding that is ultimately permeating our society.

According to a 2013 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2003, there were 32.2 reported rapes for every 100,000 people in America, a rate beat only by Bermuda (56.6), Suriname (38.2), Swaziland (72.1), and Australia (91.9). However, by 2010, while the other highest rated countries were not reported on, the rate of reported rapes in the United States dropped to 27.3 per 100,000 people, and a report from the Bureau of Justice states that sexual violence against females in the US experienced a 60% decline from 1995 to 2010.

This is not to say that violence against women or the harassment of women is not still a problem in the world. UNICEF estimates that over 200 million females in thirty different countries have endured genital mutilation, and the National Sexual Violence Resource Center still estimates that one in five American women will be raped in their lives, as well as one in seventy-one men. Our struggles with both sex and power are not nearly over, but we seem to be making steps in the right direction.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!