The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“NOBODY expects the Spanish Inquisition!… Amongst our weaponry are such diverse elements as: fear, surprise, ruthless efficiency, an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope, and nice red uniforms.”

– Monty Python

Europe used money a lot, and from the fall of the Roman Empire until the Renaissance, they didn’t use it very well. Although debtor’s prisons had been implemented throughout the Roman Empire and Ancient Greece, it was England that seemed to perfect them, or at least make them more notorious.

The idea was that once a person had racked up a large enough debt and was unable to pay, he would be locked up until he could pay it off, and he would be charged room and board. Sometimes, families of the debtors would be able to scrape up enough money to pay off the debts and get him out. Sometimes, wives and children of indebted fathers couldn’t keep up the family business and fell into poverty. And sometimes, the wives and children just got thrown in prison with the husbands as one big, miserable family.

Like the society of the time, with its common castes of royalty, nobility, and peasants, debtor’s prisons had different classes as well. If you ran in wealthy circles and had merely overextended yourself, chances are good that you’d still get some pretty decent digs while you managed to work off your debts. If you were a peasant, chances are good that you’d just get shoved into a cage with a bunch of other folks and end up dying from disease before you could complete your sentence.

Like the society of the time, with its common castes of royalty, nobility, and peasants, debtor’s prisons had different classes as well. If you ran in wealthy circles and had merely overextended yourself, chances are good that you’d still get some pretty decent digs while you managed to work off your debts. If you were a peasant, chances are good that you’d just get shoved into a cage with a bunch of other folks and end up dying from disease before you could complete your sentence.

Debtor’s prisons continued to be used for a few centuries and the idea even took hold in the New World. The United States Congress eventually deemed it unlawful in 1833, and England finally passed the Debtor’s Act in 1869, inspiring most civilized countries to give up the practice. Countries like Greece, who didn’t abolish them until 2008 and China, who didn’t abolish them until 2010, were a little behind the curve. However, considering that modern governments, even those in the good old US of A, have recently started to implement many more fines and fees to cover the exorbitant costs of our judicial systems, the practice of jailing people for not being able to pay fines is not unheard of, and has actually been on the rise.

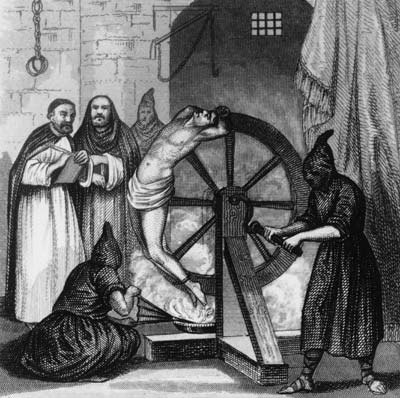

Yet as bad as it may have been to be jailed as a debtor in Medieval Europe, it was not nearly as bad as being jailed as a heretic. Perhaps it was due to early Christians being persecuted for so long, but for a people of faith, the Roman Catholic Church was extremely insecure, and if you happened to be one of the unfortunate souls who didn’t completely jive with their prescribed belief system on how to attain the love, peace, and joy of their Savior, they took it kind of personally. While the Medieval Inquisition was instituted by the Roman Catholic Church in 1184 as a way to flush out the heretics and ensure that everybody agreed with them, it wasn’t until Pope Innocent IV signed off on torture as a means of finding out what people really believed in 1252 that things got interesting.

Of course, this new institution of horrific violence wasn’t without its limits. The pope’s nickname was Innocent, after all. The inquisitors were given free rein on how to inflict the most amount of pain for the longest amount of time without the ability to draw blood or actually maim the person being tortured. This resulted in a number of radical, new torture devices like the Rack, the Thumbscrews, the Wheel, and the Fork (I’ll leave it to your imagination as to what these things did, but suffice it to say that they reached their goal of excruciating). For those convicted of being heretics, to go along with the “humane” bloodless theme, they were mercifully burned at the stake.

“Institutionalized torture in Christendom was not just an unthinking habit,” says Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, “it had a moral rationale. If you really believe that failing to accept Jesus as one’s savior is a ticket to fiery damnation, then torturing a person until he acknowledges this truth is doing him the biggest favor of his life: better a few hours now than an eternity later.”

A few more Inquisitions would rise up over the next few centuries as church leaders and the nobility struggled to ensure that everyone was on board with the orthodoxy they’d chosen to accept. And though the Portuguese and Roman Inquisitions were pretty rough on those who had to live through them, they didn’t hold a candle to the Spanish Inquisition initiated by Ferdinand and Isabella a few decades before sending Christopher Columbus off to search for new trade routes to expand their empire.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!