The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“America must be the teacher of democracy, not the advertiser of the consumer society. It is unrealistic for the rest of the world to reach the American living standard.”

– Mikhail Gorbachev

In the midst of America’s Great Depression, merchants and manufacturers were looking for ways to restore the economy. To get people working and factories operating, those who still had purchasing power needed to keep buying things, even things they may not have needed. In order to keep industrialism working properly, two things needed to happen.

First, people needed to replace things that they already owned. Through what real estate broker Bernard London called “planned obsolescence” in 1932, products started to be created so that they would eventually fail and need to be replaced. Second, the American people, and eventually the rest of the world, would need to shift their behaviors from being the thrifty citizens that were needed near the end of World War I to the voracious consumers that industrialism needed to support it.

As Peter Joseph states in his book The New Human Rights Movement, “While the Protestant, puritanical ethic of American culture has been argued as favorable to capitalist development, a view famously promoted by sociologist Max Weber, the same ethic meant that flagrant, conspicuous consumption was not a virtue. As such, commercial leaders in government knew something had to be done to change people’s values. The Great Depression brought into global question not only the US economy, but the very integrity of capitalism itself.”

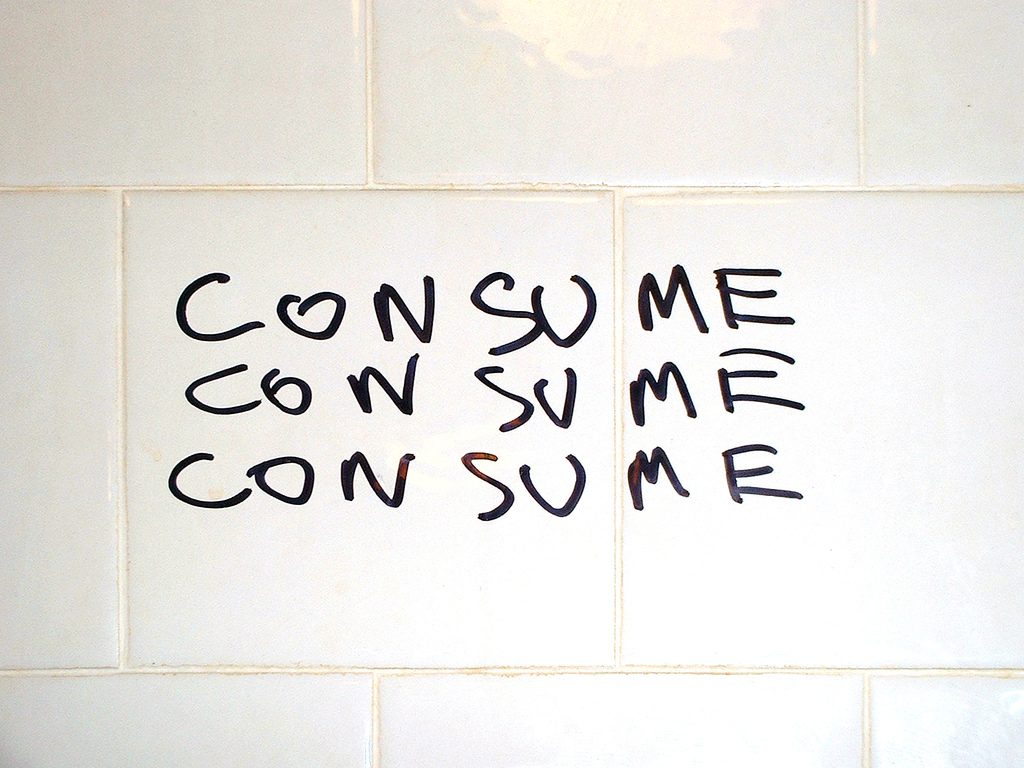

Like the “invisible hand” that is supposed to guide our economy, Adam Smith spoke briefly on the nature of consumption in The Wealth of Nations, but his idea of it being “the sole end and purpose of all production” took hold in America as well as the rest of the world. French political economist Charles Gide told his students in 1898, “The 19th century has been the century of producers. Let us hope that the 20th century will be that of consumers. May their kingdom come!” While the word “consumer” was hardly used for most of the nineteenth century, it started to take hold at the beginning of the twentieth, and by 1957, just after the American Dream had reached its peak, it completely overtook the word “citizen” as a way to describe a person living in America. Now, “consumer” is used to describe people about three times as much as “citizen”.

One of the things that contributed to this transmogrification from citizen to consumer was the development of disposable products. One of the first disposable products came in answer to a health risk. Faced with the germs that were spread through communal cups and drinking fountains, in 1907, Lawrence Luellen invented a paper cup that he called Health Kup, giving people the opportunity to avoid other people’s germs and prevent the spread of communicable diseases. The name was changed to Dixie Cup in 1919, and a hundred years later, six million trees are turned into paper cups every year for American consumption alone.

Another example of the rise in disposable products and their planned obsolescence was the light bulb. After General Electric patented their tungsten filaments in 1906, the company was striving to create the longest lasting light bulb possible with some of them lasting as long as 100,000 hours. Yet because this wasn’t offering them repeat business, several light bulb manufacturers, including General Electric, Philips, Tungsram, and others, formed the Phoebus Cartel in 1924, agreeing to limit the life of a light bulb to 1,000 hours in order to sell more products and increase revenue throughout the industry.

With the practice of “death dating” products to ensure that they would only last for a limited time, over the next few decades, our methods of consumption would grow to a dizzying degree. Cloth towels and napkins were replaced with disposable paper ones. Cloth diapers were replaced with plastic. Handkerchiefs were replaced with paper tissues. In 1950, the plastic trash bag was invented to assist us in our need to throw out the old to make room for the new.

In an article printed in the August 1, 1955 issue of Life magazine titled “Throwaway Living”, the term “throw-away society” was first used to describe our new way of living. In 1960, the styrofoam cup was introduced, and four years later, 7-11 became the first convenience store to offer fresh coffee to go, giving consumers the ability to keep moving so they could keep up with the rapid pace of working, producing, and consuming now required of them. As people waited in lines at the gas pump, disposable plastic soda bottles were introduced in 1975, their convenience and possibilities growing so popular that now 500 billion plastic beverage bottles are made every year, with only about 7% of them being recycled. Americans also throw away roughly 500 million plastic straws every day, each of them used only one time.

Another factor in the move from citizen to consumer was the contribution of the assembly line that Henry Ford introduced to build the first plethora of Model Ts in 1910.

The first Model T was priced at 950$ and cost the average Ford worker 380 days of wages to pay for. Yet, as the decade progressed, and the assembly line became more efficient, Ford cut the time for making a Model T from over twelve hours in 1912 to under two hours in 1914. By 1921, a Model T only cost 397$, and with Ford’s new 5$ per day rate, the average Ford worker could afford his very own car in eighty days. By 1925, a Ford-built automobile only cost 290$, and although there were only 6.7 million cars in America in 1919, by 1929, there were 27 million of them, almost one for every US household.

A big part of this surge in sales came through advertising. Before the 1920s, advertising was largely relegated to lots of print and not focused on any particular brands. Yet as industry leaders realized the need to have their customers keep buying, advertising agencies consulted with psychologists on ways to get more bang for their buck. By integrating practices like brand identification, slogans, and professional endorsements, US companies increased their spending on advertising to 3 billion dollars a year by 1929, five times what they spent in 1914.

As industrial designer Brooks Stevens described it, “Unlike the European approach of the past where they tried to make the very best product and make it last forever, the approach in America is one of making the American consumer unhappy with the product he has enjoyed the use of… and making him want to obtain the newest product with the newest possible look.”

By appealing to people’s vanity and insecurities, advertising became less about informing the citizenry of products that would make their lives better and more about making them feel inadequate if they didn’t stay in fashion with the latest trends. For many products, it was simply a matter of making minor modifications and advertising them as “new and improved”. For others, like the automobile, it was about adding new features every year to make last year’s model something to be despised.

“The big job is to hasten obsolescence,” said General Motors design chief Harley Earl in 1955. “In 1934, the average car ownership span was five years; now it is two years. When it is one year, we will have a perfect score.”

As Stuart Ewen put it in his book Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture, “excessiveness replaced thrift as a social value. It became imperative to invest the laborer with a financial power and a psychic desire to consume.”

With the Red Scare of communism, in which private ownership was not allowed, heeding the call of consumerism and supporting the market system came to be viewed as the highest form of patriotism. Spending money on conspicuous consumption was no longer considered an indulgence, but a civic duty in order to keep the money flowing.

Yet the hunger that has been riled in us is having more devastating effects than just wasted time and energy. “We call ourselves consumers,” Paul Hawken states in The Ecology of Commerce, “but the problem is that we do not consume. Each person in America produces twice his weight per day in household, hazardous, and industrial waste, and an additional half-ton per week when gaseous wastes such as carbon dioxide are included. An ecological model of commerce would imply that all waste have value to other modes of production so that everything is either reclaimed, reused, or recycled.”113

These days, Americans generate 70% more solid waste than they did in 1960. “Americans make more trash than anyone else on the planet,” writes Edward Humes in his book Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash, “throwing away about 7.1 pounds per person per day, 365 days a year. Across a lifetime that rate means, on average, we are each on track to generate 102 tons of trash. Each of our bodies may occupy only one cemetery plot when we’re done with this world, but a single person’s 102-ton trash legacy will require the equivalent of 1,100 graves. Much of that refuse will outlast any grave marker, pharaoh’s pyramid, or modern skyscraper. One of the few relics of our civilization guaranteed to be recognizable twenty thousand years from now is the potato chip bag.”

Not only are we filling our landfills with the 95% of plastics that are produced as single-use items, but due to the increased volume of planned obsolescence and our newfound obsession with technology, we also throw away television sets, computers, smartphones, and millions of tons of e-waste every year. Although it is only estimated to make up roughly 2% of our landfills, e-waste and the precious metals that are thrown away with them, comprise about 70% of the toxic materials in our landfills.

“Ecologically, this means capitalism is structurally oblivious to humanity’s existence on a finite planet,” says Peter Joseph. “The system was to produce, not to conserve. In fact, if you think about it, you will discover an interesting paradox to market logic: the fact that capitalism is a scarcity based economic system that actually seeks infinite consumption.”

There were times when Americans simply fixed things when they broke. In the 1940s there were roughly 60,000 shoe repair shops, yet though there are many more shoes these days, there are about one-tenth the number of repair shops. And one would be hard pressed to find a place to have a television fixed. In order to continue this trend and keep selling products, it was recently discovered that Apple programmed the iPhone 6 to cease functioning and turn into a relatively useless “brick” when owners tried to have them fixed.

Yet, while it was once seen as our civic duty to throw things away and purchase new things in order to help the economy grow, there is a growing movement of people in America who see better ways of serving the community. There are many who would rather start fixing things again instead of seeing them thrown away.

“According to a number of recent commentators,” says Frank Trentmann in his book Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First, “we are already living in the twilight years of the empire of things. They announce the coming of ‘dematerialization’ and ‘post-consumerism’, marked by a growing interest in experiences, emotions, and services, a revival of repairing, and the spread of leasing initiatives and sharing networks enabled by the Internet. By 2015, almost a thousand repair cafés had sprung up in the richest corners of consumer societies in Western Europe and North America.”

While there are some who wish to embrace a more healthy form of materialism, one in which material is actually valued instead of wantonly disregarded, it may be quite an uphill struggle to overcome the power of the market economy and the convenience of consumerism.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!