The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

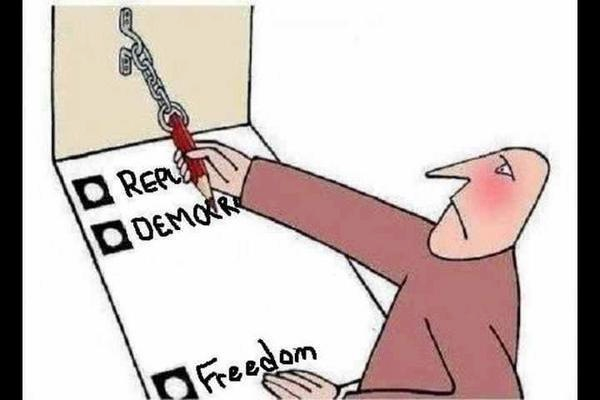

“I don’t like either political party. One should not belong to them – one should be an individual, standing in the middle. Anyone that belongs to a party stops thinking.” – Ray Bradbury

When Congress started meeting in 1789, each member received a daily stipend of 6$ until 1795, when Senators started getting 1$ a day more. In 1855, they put themselves on salary at an annual rate of 3,000$ a year, and have had about forty pay adjustments since, building to their current base pay of 174,000$ a year.

In the early days, being a member of Congress was a sacrifice. Meeting in three sessions over the first two years, these public servants had to travel long distances, being away from their families and means of livelihood for long lengths of time. One third of them resigned within the first few years. These days, however, with the base salary of a member of Congress being over six times the median salary of a US citizen (28,851$),39 and the multiple streams of auxiliary revenue the office helps create, the job has gotten a bit less sacrificial.

Still, serving as a member of Congress was quite an honor, and the new politicians did a great deal of grandstanding and speech-making as they carved out their legacies, causing James Madison to remark, “Scarcely a day passes without some striking evidence of the delays and perplexities springing merely from the want of precedents.” Yet considering the precedents they were setting in the fledgling republic, the considerable amount of time devoted to committees and debates would eventually pay off.

In the first session of Congress, they passed acts on administering state and federal oaths of office, tariffs on goods, foreign affairs, the Department of War, the Department of the Treasury, and the court system. In the second session, they made provisions for the first Census, citizenship, patents, criminal procedure, copyrights, the seat of the US government in Washington DC, and regulation for commerce with the natives. In the third session, lasting only three months compared to the six-month long first session and eight-month long second session, they established the First Bank of the United States, granting it a twenty-one year monopoly on printing money. They also devised the Whiskey Act, an attempt to tax alcohol which resulted in a rebellion among the farmers who were producing their own corn squeezin’s and was repealed when Thomas Jefferson became president ten year later.

Throughout the proceedings, Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, who were both part of Washington’s cabinet as Secretary of State and Secretary of the Treasury, respectively, often found themselves in vehement disagreement. Hamilton wanted to find money and investors to help pay off the debts from the war, and Jefferson was looking out for the common men. Although the first Congress had their share of debates, they were very nervous about partisanship, and the schism between these two men caused quite a bit of consternation as many of the Founding Fathers did not want to break Congress into parties.

Years before the Constitution was even written, John Adams said, “There is nothing I dread so much as a division of the Republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader and converting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.”40

Washington, in his farewell address, followed up the sentiment that he feared the possibilities of political parties, “to become potent engines by which… unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.”41

Unfortunately, although Adams, Madison, Hamilton, and the rest of the key players were initially against parties, by the time Washington left office, two parties had already formed. Adams and Hamilton led the Federalists, and Jefferson and Madison led the Democrat-Republicans. As years went on, these two parties would morph into the Democrats and Republicans that we know today, but throughout their evolution they have had a few different variations and incarnations. Unfortunately, although the Founding Fathers initially rallied against it, and though dozens of other parties would come into existence, the US Congress would never move past the two party system that Washington feared would “enfeeble public administration” through “the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities… itself a frightful despotism.”

Unfortunately, although Adams, Madison, Hamilton, and the rest of the key players were initially against parties, by the time Washington left office, two parties had already formed. Adams and Hamilton led the Federalists, and Jefferson and Madison led the Democrat-Republicans. As years went on, these two parties would morph into the Democrats and Republicans that we know today, but throughout their evolution they have had a few different variations and incarnations. Unfortunately, although the Founding Fathers initially rallied against it, and though dozens of other parties would come into existence, the US Congress would never move past the two party system that Washington feared would “enfeeble public administration” through “the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities… itself a frightful despotism.”

Despite the fact that the Constitution spoke nary a word about political parties, the Democratic Party was officially established in 1828 and the Republican Party was established in 1854. Although they have managed to come together and accomplish some bipartisan endeavors, in the latter half of the twentieth century, the squabbles became much more heated and the polarization much more extreme.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!