The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“No complaint… is more common than that of a scarcity of money.” – Adam Smith

When the settlers in the New World weren’t slaughtering natives to increase economic expansion by assuming control of their land, they were learning new ways of expanding their economy. Wampum was one such lesson.

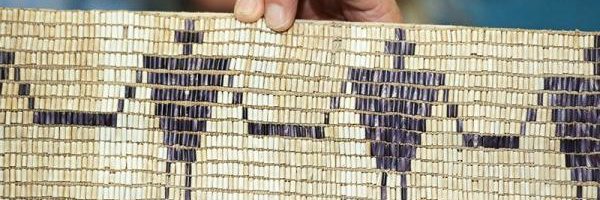

“Modern economists would call wampum a primitive money,” says Jason Goodwin in Greenback: The Almighty Dollar and the Invention of America, “perhaps they mean it wasn’t managed by economists. The colonists also saw it as primitive money, and that meant they could make it work better. They set a wampum exchange rate into shillings and pence, according to the furs it bought, and adopted what they took to be Indian reckoning, by which one black bead was worth six white. From an Indian perspective wampum wasn’t primitive money at all: it wasn’t exactly money, and it took some skill to produce. Wampum had considerable value in native society, but not for what it could buy or sell. Woven into patterned belts, wampum bore witness to a variety of exchanges. Dutch and English colonists instinctively focused on the number of shells in a belt, but the Indians gave consideration to the patterns, the feel and presence of the belts themselves, as they were given and received in ceremonies to mark treaties, signify valor, or to display the rewards of high status. The patterns formed a kind of mnemonic, suggestive of old agreements and encounters. On the proper occasions the stories on the tribes’ belts were told by the elders. Powerful men took them to the grave. The loss of a wampum belt was a wound to the identity of the tribe.”

Each bead had its own worth, and over the course of the next few centuries, the clever Europeans devised a number of ways to monetize the beads and trade with them. Although New England ceased using wampum as legal tender in 1661, Stuyvesant still used them to finance the construction of the New York citadel, and a number of states, like North Carolina and Massachusetts, had their turn at using wampum as legal tender.

Wampum fluctuated in both its popularity and legality, but in 1760, the first wampum factory was opened in New Jersey. Prized both as a currency and as ornamental decor, the production of wampum kept the factory open for 100 years, but the increase in production caused inflation, drastically detracting from its value. But that didn’t mean that the settlers didn’t come up with other means of money, however, the King of England wasn’t too happy about it.

When settlers left England for the New World in 1620, they were compelled by the desire for religious freedom. Since the King had started the Church of England and scooped up the monastic properties for himself as a way to stop having to pay the Pope, the religion of the Church of England, as it was for the Roman Catholic Church from which it spawned, was obsessed with money. Money was about control, and the King wasn’t about to lose control over his constituents abroad, so he forbade them from making their own money, limiting their purchase power to using only English bills to buy only English goods.

Nevertheless, the adventuresome lot that had crossed the sea came up with a few ingenuities that would still let them play the money game. Most of them simply bartered, exchanging pelts, food, ammunition, and pretty much anything else they could find. However, Massachusetts was a bit more clever in their approach.

Since British Law dictated that only the King could mint coins, the New Englanders took advantage of King Charles’s beheading and started minting silver coins with the date 1652, a year when there was no King, and England had become a republic. Nevertheless, by 1682, England had a new king who put a kibosh on the operation and shut the mint down.

Of course, that didn’t stop Massachusetts. In 1690, they started printing paper money, calling them “bills of credit.” It wasn’t the first time that paper was used as a currency in the New World. Back in 1619, Virginia had realized how well tobacco grew, and due to the popularity of the pleasure-inducing plant, they started using it as a tradeable commodity, incorporating promissory notes to assist in the dealings.

But the notes weren’t used nearly as much as the tobacco itself. As folks back in England started to get a taste for the stuff, demand grew, and tobacco became the staple crop upon which multiple laws were based in the development of the New World’s governing bodies. Although “big tobacco” is often derided today, tobacco was largely the foundation for America’s economic system, with England importing roughly 20,000,000 pounds of the stuff annually by the end of the 17th century.

Like wampum, tobacco didn’t start out as a commodity. Native Americans revered the plant for its medicinal qualities, using it to help with earaches, toothaches, enemas, and as a treatment for colds. In addition, when smoked in large quantities, the plant had hallucinogenic effects, making its use sacred among the natives, who used it as an entheogen and a portal for greater spiritual connection.

Nevertheless, like wampum, the early settlers saw its commercial appeal, and expanded upon its use, taking it from sacred plant to staple crop. For the next two hundred years, as tobacco grew in popularity throughout Europe, the settlers used the plant to pay taxes, buy slaves, and purchase just about anything that wasn’t nailed down. Although there was a moral contingent that stood against tobacco, and it was at one time illegal to smoke in public in Massachusetts, people throughout the New World were taking up the habit of using tobacco for money faster than they took to smoking it, and smoking it they certainly were.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!