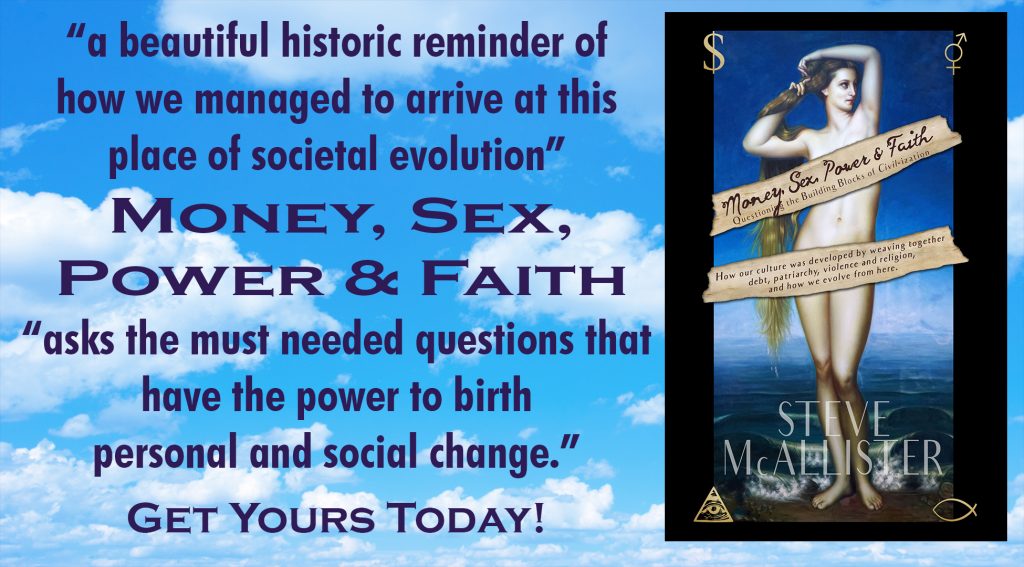

The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“Remember, remember always, that all of us,

and you and I especially,

are descended from immigrants and revolutionists.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt

As King James argued for his divine right as king, ignoring Parliament and continuing his persecution of witches, Baptists, Puritans, and Quakers, many were seeking a way out from under the tyranny. In addition, an overcrowded England was encouraging people to establish colonies in the New World, a venture that offered all new opportunities for those willing to invest their lives in the growing economic adventure of wealth creation. Already, early explorers were developing inordinate amounts of wealth from growing sugar on the Caribbean islands, and as tobacco started to sprout in Jamestown and the surrounding areas, the move to the New World was made all the more tempting.

On September 16, 1620, 102 people set sail on the Mayflower. The journey was partly funded by a group called the London Adventurers, with an agreement that the entrepreneurs would receive a share of the profits from the venture, and part by the Virginia Company for the 30 or so Separatists seeking religious freedom. The plan was to settle just north of Jamestown as a part of the Virginia Charter, but they were thrown off course and first landed on what is now Cape Cod. When they ultimately decided to start building on the shores of Plymouth Harbor, they reasoned that the Virginia Charter didn’t cover Massachusetts and decided to write what is often considered the first American constitution. The Plymouth Charter offered the colonists the opportunity to practice self rule, the first experiment with democracy in the New World.

The idea that England’s wealthy class could financially benefit by paying people to emigrate to the New World, and set up businesses on the land they assumed control over, led toward the investment in one of the world’s first major advertising campaigns, the advertising of America. As the poor who could find little work on the overpopulated island were promised new lives and opportunities to become wealthy, three and a half million people emigrated from England to the New World over the next two centuries. Some of the immigrants were entrepreneurs, and some were indentured servants who would be required to pay off their passage through manual labor, a practice that would become unfortunately intertwined with the growing slave trade. Although many found success through the benevolence of their investors, many were treated inhumanely and fled from their debt-holders.

The rate of runaway servants became so common that when the Boston News Letter became the first regularly published American newspaper in 1704, they offered the opportunity for advertising for “all Persons who have any Houses, Lands, Tenements, Farmes, Vessels, Goods, Wares, or Merchandise, & cc. To be sold or Lett, or Servants Run away.” The disrespectful relegation of humans beings as nothing more than capital was evident in ads like Samuel Linton’s in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1784:

The twenty-fifth of this September,

I would have you well remember,

My ‘prentice boy he ran away,

Was sixteen years of age last May;

His name James Clift, his visage light,

And likes to ramble in the night,

Above five feet six inches high,

And very apt to swear and lie,

The smaller pox has left its trace,

And may be seen upon his face.

Next, I’ll describe the clothes he wore,

And others that away he bore.

The coat was brown, his jacket blue,

The hat he wore was almost new.

This sense of entitlement that the wealthy held over the poor was nothing new to the New World, nor was it necessarily anything remarkable, as people had been assuming power over others for millennia. Yet the stance of elitism, from the beginning, was ingrained into the developing culture through a myriad of influences. From the slave traders that first arrived upon these shores to the landowners with indentured servants to the Pilgrims’ religious idea of predestination, that they were all among the elite chosen by God, there was an inordinate amount of ego-boosting going on during the setting of America’s foundation. It may very well be why pride is seemingly held as one of the highest virtues in America today.

Unfortunately, blending this entitlement with the most extraordinary emigration movement in the history of our species served to develop a new way of community development which ultimately built on the sense of separation. Before humans started monetizing land, and even as we did and came to live on the Commons together, villages were developed with families in mind so that people always lived around people that they knew and loved intrinsically. First in the new world of monetized civilization, and even more so in the New World of America, people were no longer living among family, but among strangers.

Real estate had long been sold to those who wished for the elitism of nobility. For a while, the State respected the land known as the Commons, where people could still live together in harmony. Eventually, that land was taken over by those who considered themselves noble, and humanity fully adopted the ideology that if you’re going to live somewhere on this planet, you’ve got to pay somebody for it.

Due to our proclivity to give such high regard to this thing called “real estate,” we adopted what Laurence Brandt calls “the little king myth.” The ownership of property came to fruition based upon this “divine right of kings” even before Henry started to argue for it, developing land into a commodity owned by the nobility, those who assumed priority over the rest of humanity. As we have perpetuated it, although it has offered many of us the security we long for since we started to hold accounts against each other, it has also been very instrumental in our own enslavement.

As Boldt states in his book Zen and the Art of Making a Living, “The great fallacy of the little king myth is its suggestion that the individual ego is a thing apart – apart from nature, from the spirit of life, from his fellows, and even from his own psyche. To conceive of ourselves as separate is to create an artificial boundary between ‘me’ (the ego) and ‘them’ (everything and everyone else). Our separate kingdoms become our prisons. We can’t lock ‘them’ out without locking ourselves in. Individual alienation and social and environmental conflict must result from this separative consciousness.”

Even the regular king myth has its fallibilities. As James’ son, Charles I, attempted to use his divine right of kingship to levy taxes without the consent of Parliament, many of the people of England stood against the noble’s perceived right, resulting in The English Civil War. Started in 1642, the war resulted in the execution of King Charles I for high treason, and although his nineteen year old son, Charles II, was ready to take the throne, Parliament declared England to be a Commonwealth, dispatching the monarchy for the next eleven years.

Charles II would eventually become king, after living in exile for the decade, but the damage had already been done. Although the “little king myth” had already been carried to the New World as settlers sought to establish their miniature kingdoms, the idea of the republic, a rule beyond mere monarchy had also been planted as a seed. And as the English monarchy set out to reestablish its rule, the unrivaled authority of the king would fall short again.

In the meantime, the monarchy had some stuff to take care of. One of the most important matters was that of the military. France had recently defeated them at the Battle of Beachy Head in the Nine Years War, and it was agreed that England needed a better navy. To pay for it, England created a privately owned bank, allowing them to procure the funds that would make them the strongest military might for the next two centuries.

Unfortunately for them, it wasn’t mighty enough.

As settlers were establishing a livelihood in the New World among the new strangers that had become their neighbors, they wanted more ways to trade. However, despite numerous requests, including a personal visit to London by Benjamin Franklin, Parliament forbade the colonies from printing paper currency to assist in building a stronger economy. The thinking was that England would lose control of the revenue and not see the profits they had hoped for, but by holding so tightly, they eventually lost hold altogether.

By 1775, the colonists had had enough of England’s imposed limitations and taxes, and the new republic was born.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!