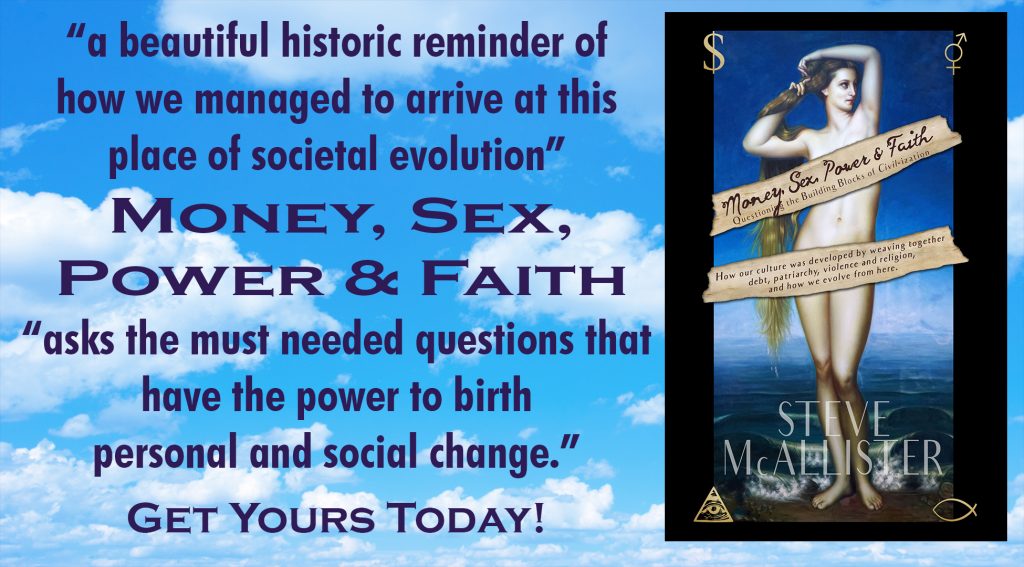

The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“Can anybody remember when the times were not hard and money not scarce?” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

When we started using money as a means of manipulating control, the practice started in ledgers. The notations that were made symbolized a herd of cattle or a bushel of grain, but the money in itself, the actual means of exchange, was merely a virtual abstraction, just numbers on a page. Over the last century, we have come to associate the dollar as the symbol of money, with some of us conjuring images of coins as well.

However, more and more, we seem to be reverting back to using money in the virtual realm, in electronic ledgers. In 1860, Western Union revolutionized the process by instituting the electric fund transfer through the telegram. The game was changed once again in 1946, when a banker named John Biggins released the “Charg-it” card.

Although Biggins’ contribution would come to evolve into the modern credit card, in another case of life imitating art, the credit card was actually conceived in 1887 by Edward Bellamy in his novel Looking Backward. As many who imagine a utopian future, there is generally an imagined means for citizens to have their needs met, allowing them to go provide for their wants. While our culture tends to favor the wants of a few while the needs of many go unmet, Bellamy had a vision of a “credit card” that was used eleven times in his novel for spending the dividends that each character received from the government.

Biggins’ vision was not quite as bold. Building on the idea that was already in practice by companies like Western Union, American Airlines, and a number of oil companies and department stores of issuing cards for frequent customers, Biggins’ merely worked with some of the local businesses to allow his customers the ability to use his card in their stores.

A few years later, in 1950, the Diner’s Card was released as a cardboard card that could be used as an alternative to cash, primarily to pay for travel, food, and entertainment. In Paying with Plastic: The Digital Revolution in Buying and Borrowing David S. Evans writes, “At the time, individual stores issued charge cards — something like credit cards that would allow you to pay on installments. But if you were shopping, let’s say, in New York, you would have to carry around many different cards. So this created a card that people could use at many different merchants.”

Diner’s Club was an instant hit with more than 20,000 cardholders after just the first year. By the end of the decade, American Express, which was initially a competitor for the US Postal Service and had previously released both the traveler’s check and the money order, got into the charge card game as well, launching the first plastic card, although they wouldn’t release an actual credit card until 1987. In 1966, the BankAmericard (which would eventually become Visa) and MasterCard were both released.

According to the 2014 Census Bureau, 167 million Americans have at least one credit card, and these four credit card networks currently account for 546 million credit cards. However, they are actually waning in popularity. Because a lot of people are wanting to move beyond a debt-based existence, many are paying off their credit cards and opting not to use them again. Many others are simply finding more efficient ways to pay for things.

In the early nineties, Dr. David Chaum, a cryptologist who had excelled at anonymous communication, developed the eCash software, opening the world up to electronic payments through the World Wide Web. According to the Federal Reserve, by 1995, 90% of the total value of all American transactions were made through electronic payment,65 four years before the release of PayPal. In 2009, Bitcoin was introduced, ushering in the blockchain as a digital record-keeping system, with the hopes of moving beyond using the dollar as the foundation for every transaction.

Many have warned of Bitcoins and the other cryptocurrencies which have since been spawned, and fortunes have already been made and lost as people have used their regarded value to buy and sell. Many others have concerns over the amount of energy it takes to record these transactions, with estimates that by the year 2020, it will take as much energy to power the Bitcoin market as it currently does to power the entire United States. Yet Bitcoins may simply be as fuel efficient to cryptocurrencies as the Model T was to automobiles.

While some question the actual value behind the hundreds of cryptocurrencies that have been created, and view them as little more than fiat currencies, the development of the blockchain is already being used to keep records of production and distribution in a number of industries. Developers are now seeking ways in which the blockchain can be incorporated into our daily transactions to help us do a better job of tracking who did what and who has what.

In recent years, the advent of smartphones has offered even more ways to spend and receive money, like the iPay system, which now allows people to pay with only a swipe of their phone. And the new Amazon Go store tracks purchases through cameras and sensors, charging items to a registered credit card to avoid buyers having to check out.

Ultimately, beyond all of the fancy means through which we have celebrated money – beyond shekels, coins, paper money, and plastic – this game of money is still merely a system of record keeping. Unfortunately, it doesn’t keep adequate records for life beyond the limitations of the monetary construct.

If we are to consider that the entirety of the planet Earth is simply here for the use of humans, it may seem feasible for us to use money to account for how much each of us uses, but even in that narrative, the monetary system is still ill-equipped to account for all that the planet has to offer. Nor does it adequately account for the needs of true people and the true resources they have to offer. Nevertheless, given the power at each person’s disposal to now more effectively share information and instantaneously conduct transactions, we do have the means to more greatly collaborate on the projects that are of greater importance to us, and fix what our boyish games of competition have broken.

Yet we will still have to contend with how those games of competition have resulted in the majority of the wealth being concentrated into the accounts of a few.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!