The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“I hope we shall crush in its birth the aristocracy of our monied corporations which dare already to challenge our government to a trial by strength, and bid defiance to the laws of our country.” – Thomas Jefferson

After corporations saw a resurgence in the Middle Ages, their use was refined in the 18th century. In developing its use in England in 1793, Stewart Kyd wrote in A Treatise on the Law of Corporations that a corporation was “a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having perpetual succession under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual, particularly of taking and granting property, of contracting obligations, and of suing and being sued, of enjoying privileges and immunities in common, and of exercising a variety of political rights, more or less extensive, according to the design of its institution, or the powers conferred upon it, either at the time of its creation, or at any subsequent period of its existence.”60

As corporations were adapted to life in the United States, individual states were initially able to impose their own conditions on them, limiting their abilities and making them more manageable. Some corporations were granted charters for only a limited time, as they were initially intended during the Roman Empire. Some were not able to own property or stock in other corporations, and some were forbidden from participating in political activity.

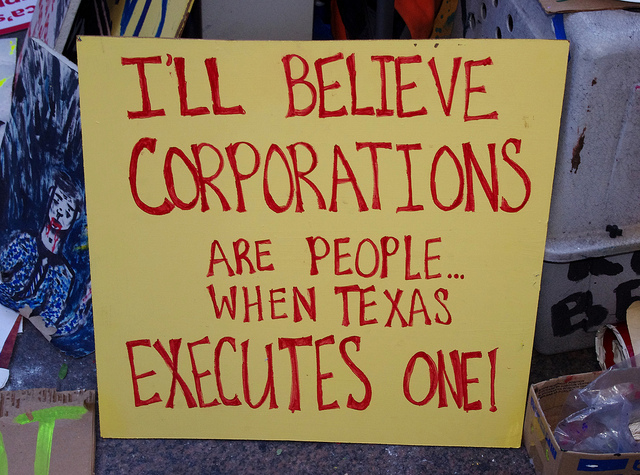

Yet as the use of corporations became more ingrained into the culture, many of these limitations fell by the wayside as corporations helped establish a more vibrant economy and buoyed the fervor of capitalism. In 1818, the United States Supreme Court first granted a corporation the same rights as a natural person to enforce a contract in the case of Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward. Decades later, in the case of Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, the Supreme Court reiterated the notion that corporations had legal standing and were protected as people under the Bill of Rights.

But it wasn’t until Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that the Supreme Court would loudly and proudly declare the personhood of corporations and the rights that these faceless entities had as citizens. Despite the limitations that had been placed on corporations, and the role they could play in the political arena through the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, the 1974 Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments, and the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, the non-profit organization Citizens United wanted the ability to launch an anti-Hillary Clinton campaign. Their efforts to promote partisanship through propaganda ensured that the rights of personhood were not only extended to non-profit corporations, be they benevolent or benign, but they were also granted to for-profit corporations. It was this decision that summarily opened the floodgates for corporate monies to openly infiltrate the democratic process and push the United States government from aristocracy to oligarchy.

Paul Hawken describes a corporation as “a social machine with interchangeable parts and processes that can be measured, predicted, manipulated. They can be bought and sold, broken up and reassembled. Because managers manage corporations, it is difficult to see that corporations also run themselves. They have a powerful inertia toward given goals, and if one manager cannot accomplish those goals, he or she is very likely to be replaced until one is found who can. A corporation, like other technologies – nuclear power plants, airplanes, and vacuum cleaners – has an inherent, internal logic that transcends what you and I may think it is. It has a life of its own, especially since ownership can be diffused, broken into pieces, sold and inherited, and is essentially fungible. A corporation, although created and peopled by human beings, does not depend on any of them in order to exist. Founders die, so do their families; directors and managers come and go; workers have become essentially interchangeable components, particularly where the work involves repetitive, industrial tasks. In short, corporations are not quasi-sacred institutions like the PTA. We should think of them as a useful technology that we can employ to accomplish productive, economic tasks, nothing more, nothing less.”

In 1776, there were 2.5 million people and 7 corporations in America. In 2015, there were 321.4 million people and 9 million corporations. Although it sometimes seems dire as our system is getting mired in corporate control, it should also be noted that the US also now has roughly 23 million sole proprietorships, a number that has been steadily on the rise since 1980, when there were just over 5 million sole proprietorships and more C corporations than exist today. Granted, there are probably fewer C corps because they have all been merging into monopolies, yet the steady rise in entrepreneurship reveals a population still in touch with its healthy roots of independence and ingenuity in a truly free market.

The original purpose for a corporation, as it is with many man-made machines, was to serve a purpose for the betterment of human society and be dissolved when the need was met. It was not the intention of the creators of the corporation for us to become so dependent upon these tools of thought that we would reach the point where we are living to serve them. The purpose of these imagined entities was merely to coordinate the activities of humans to achieve a common goal and be rewarded in the process.

Yet many of us have begun to imagine them as some sort of eternal beings upon which our very survival depends, and some of us have made the reward more important than the true goal of service to humanity. And to the detriment of our entire existence, many of those corporations do nothing more than turn resources into money with no true value. It is time that we give some more thought to what corporations truly are, what functions they are truly capable of serving, how long they should be empowered to fulfill said functions, and what assortment of endeavors conscious entrepreneurs can involve themselves with which to create the most effective changes in their communities and most diverse channels of residual financial flow as rewards for their realization of abundance.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!