The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

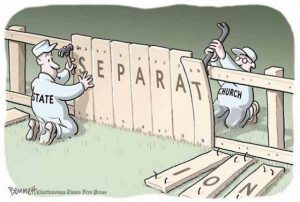

“I’m completely in favor of the separation of Church and State. My idea is that these two institutions screw us up enough on their own, so both of them together is certain death.” – George Carlin

Back in the United States, the colonists were also embracing the merits of hard work. With a more balanced economic equality and a less stringent role for the Church, things seemed to be moving along rather nicely. Though there is still speculation as to the exact religious convictions of America’s founding fathers, it is strongly established that many of them offered little reverence to religious matters and had adopted less demanding offshoots of the Christian traditions in which they were raised. Many of them fought vehemently for the separation of church and state.

James Madison was publicly silent about his religious convictions, but it is believed he was a deist, which guided him toward an acknowledgment of a Supreme Being less concerned with the trappings of dogma. As he contributed greatly to the Constitution, and the accompanying Federalist Papers which would help it to be ratified, he, as with many of the other contributors, did not want to create another intrusive government like the monarchy from which they had fought so hard to escape. Imposing adherence to organized religion, as it continued to unravel in the wake of the Enlightenment period, did not seem like a prudent course of action to achieve their goal of an enlightened society. Madison said, “Every new and successful example of a perfect separation between ecclesiastical and civil matters is of importance.”

Yet there were also some who adamantly believed that Christianity was the cornerstone of civility, and that even though it was not versed in the government’s new scriptures, there was still a prevalent Christian theme. As John Adams said, “The highest glory of the American Revolution was this: it connected, in one indissoluble bond, the principles of civil government with the principles of Christianity.” His son, John Quincy Adams went further to say, “The Declaration of Independence laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity.”

Although our second and sixth presidents held dearly to their religious tradition, our first president was not such a fundamentalist. One of the reasons that George Washington was selected for the role was his pragmatism and even-headedness. In drafting the Treaty of Tripoli, to assuage the concerns of the Muslim state, he wrote “The government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

Raised as an Anglican as many of the founding fathers were, Thomas Jefferson encouraged religious freedom as he did in a letter to his nephew, stating, “Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.” Conservative in sharing his religious beliefs publicly, Jefferson didn’t subscribe to many of the beliefs in the Nicene Creed that had guided the Christian religion for so long. As with the other deists, like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Ethan Allen, and James Monroe, Jefferson didn’t believe in the more mythical aspects of Christianity, such as the virgin birth, Jesus’ divinity, resurrection, and the miracles he performed, or even that the Bible was divinely inspired.

In a letter to John Adams, Jefferson wrote, “The day will come when the mystical generation of Jesus by the Supreme Being in the womb of a virgin, will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter… But we may hope that the dawn of reason and freedom of thought in these United States will do away with all this artificial scaffolding.” Jefferson still had a great reverence for the message of Jesus, and went so far as to publish his own version of the gospels, editing out the “artificial scaffolding” of miracles and mythology, and giving greater acknowledgment to the teachings that spoke directly to human reason, calling it “The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.”

Due to the extensiveness of the role that religion had played in limiting personal sovereignty, the founding fathers were under great compulsion to ensure that such a thing would not happen again, so much so that when the Constitutional Convention gathered to draft the most important legislative measures of their time, first and foremost was the separation of Church and State. The very first rule of the very First Amendment stated that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Impeccable to this detail, as the Constitution was written, there was no reference to God or any Christian influence beyond the mention of the Creator, a form of vague recognition that ran throughout the writings of the founding fathers as a nod to the concept of a “Supreme Being,” “The Almighty,” or “Supreme Architect,” as Washington called It.

However, that didn’t stop the states from establishing their own relationships with religion. As states developed their own constitutions, some doubled down on religious freedom, and some added in more exclusive provisions.

However, that didn’t stop the states from establishing their own relationships with religion. As states developed their own constitutions, some doubled down on religious freedom, and some added in more exclusive provisions.

“The legislators of Connecticut begin with the penal laws, and, strange to say, they borrow their provisions from the text of the Holy Writ,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. “’Whosoever shall worship any other God than the Lord,’ says the preamble of the Code, ‘shall surely be put to death.” This is followed by ten or twelve enactments of the same kind, copied verbatum from the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy – blasphemy, sorcery, adultery, and rape were punished with death; an outrage offered by a son to his parents was to be expiated by the same penalty. The legislation of a rude and half-civilized people was thus applied to an enlightened and moral community. The consequence was, that the punishment of death was never more frequently prescribed by statute, and never more rarely enforced.”

New Jersey’s constitution stated that “no person shall ever… be deprived of the inestimable privilege of worshiping Almighty God in a manner agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience,” and New Hampshire’s 1784 constitution expanded on the notion, stating “Every individual has a natural and unalienable right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and reason; and no subject shall be hurt, molested, or restrained, in his peers on, liberty, or estate, for worshiping God in the manner and season most agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience; or for his religious profession, sentiments, or persuasion; provided he doth not disturb the public peace or disturb others in their religious worship.”

Maryland was a bit more selective in who should receive religious freedom, ensuring that “All persons, professing the Christian religion, are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty.” Georgia went even further by dictating that representatives be of the Protestant religion while Delaware required anyone holding public office to profess their faith in “God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God blessed for evermore” and to “acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.”

When North Carolina wrote their constitution in 1776, they declared the state’s religious bias, declaring, “No person who shall deny the being of God, or the truth of the Protestant religion, or the divine authority of the Old or New Testaments, or who shall hold religious principles incompatible with the freedom and safety of the State, shall be capable of holding any office or place of trust or profit in the civil department within this State.”

South Carolina’s constitution held that “All persons and religious societies who acknowledge that there is one God, and a future state of rewards and punishments, and that God is publicly to be worshiped, shall be freely tolerated” and that “the Christian Protestant Religion shall be deemed, and is hereby constituted and declared to be, the established religion of this State.” Even today, the South Carolina constitution forbids any office holder from denying the existence of a Supreme Being.

While the argument can be made that the United States of America was not established as a Christian nation, it was a nation comprised of many Christian states. Yet although many of the policy makers adhered to incorporating religious sentiment into the law of the land, only about 10-20% of Americans were devoutly religious around 1776, a statistic that would certainly change over the next few centuries as people were given the freedom to form new denominations and worship styles.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!