The following is a chapter from Money, Sex, Power & Faith.

Order your copy in paperback or for Kindle!

“[A] great embarrassing fact… haunts all attempts to represent the market as the highest form of human freedom: that historically, impersonal, commercial markets originate in theft.”

– David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years

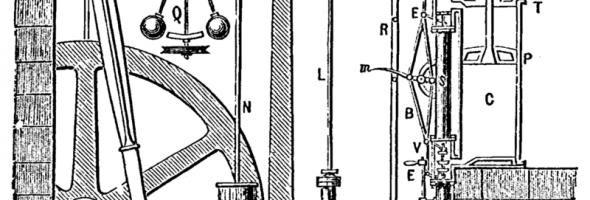

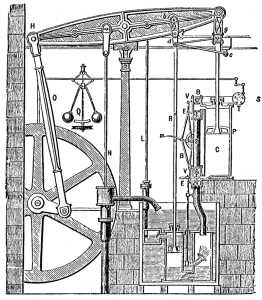

Capitalism seemed to be working quite well back in the old country… but not quite as good as it could have. While teaching at the University of Glasgow, Adam Smith befriended the university’s mechanic named James Watt, who, while repairing a Newcomen steam engine, thought that it could be improved. Although Watt embraced Smith’s version of capitalism, he ignored the part about monopolies being a bad thing and eventually hindered any more improvements to the steam engine for another quarter century.

As fruitful as it may have been for Boulton and Watt, for the other entrepreneurs waiting to engage the new technologies, this first blossom of capitalism in action wasn’t quite as fruitful as Smith had foretold.

When he made the initial improvement, Watt wasn’t in a very good place. His wife had died in childbirth, and he was carrying considerable debt when he met Matthew Boulton in 1775. After inheriting his father’s toy company, Boulton reveled in entrepreneurship, and helped Watt to refine his engine, patenting each and every improvement he made. Perhaps it was based on the hardships that he had endured, but Watt protected his engine and clung to the rights to it, readily taking to court anyone who would implement his improvements in the further development of the steam engine.

Unfortunately, Watt’s desire for control was not necessarily the virtuous spirit of competitive ingenuity described by Adam Smith. Instead, his heavy hand and the monopoly it created slowed progress and hindered ingenuity, for himself and the rest of the innovators wanting to get involved in the revolution. At a time when Watt could have implemented the crank and flywheel patented by James Pickard, it would seem that his patent-grubbing karma forced Watt to start from his own scratch, and basically waste time manipulating the improvement by calling his less efficient version a “sun and planet” gear instead of just collaborating with Pickard on a better engine for all involved.

Smith’s ideas on competition seemed to carry a lot of merit, yet to make the laws of capitalism work smoothly, even competition must be practiced in a collaborative fashion, working toward the virtues of the greater good. While it is true that Watt is given mythic credit for his role in the Industrial Revolution, and his rags to riches story that accompanied it, we can only wonder how differently this time of progress would have progressed had his virtue of self-interest not been so pronounced. Although Watt’s engine used three times less coal than the Newcomen engine, due to his tight control of his patents, fuel efficiency hardly changed for the steam engine until Watt’s patents expired in 1800, when other innovators were able to improve upon the designs, and fuel efficiency increased fivefold over the next few decades.

Smith’s ideas on competition seemed to carry a lot of merit, yet to make the laws of capitalism work smoothly, even competition must be practiced in a collaborative fashion, working toward the virtues of the greater good. While it is true that Watt is given mythic credit for his role in the Industrial Revolution, and his rags to riches story that accompanied it, we can only wonder how differently this time of progress would have progressed had his virtue of self-interest not been so pronounced. Although Watt’s engine used three times less coal than the Newcomen engine, due to his tight control of his patents, fuel efficiency hardly changed for the steam engine until Watt’s patents expired in 1800, when other innovators were able to improve upon the designs, and fuel efficiency increased fivefold over the next few decades.

For the time during the Boulton Watt monopoly, the pair weren’t even manufacturing steam engines of their own, and didn’t start until after their patents expired. Innovating on the tenets of capitalism, they instead charged licensing fees for the technology, hiring independent contractors to perform the labor, and building up quite a bit of a nest egg in the process.

Even the seemingly non-selfish activities of Boulton and Watt were grounded in selfishness. By establishing the Soho Friendly Society and making membership mandatory for the men and young boys that worked for them, they took one sixth of the workers’ compensation, introducing an insurance program that would cover the workers’ expenses in case of illness or injury. This model would serve as the foundation for insurance programs to come, ensuring that none of their employees fell into the pockets of poverty that were erupting throughout England “except a few irreclaimable drunkards”31 that still sought assistance from the Church as they blew off their own steam.

However, those in the Church, throughout its various factions, were also growing to embrace the tenets of capitalism, seemingly more than the tenets of Christ. As industry increased, and creating a livelihood grew more complex, it was largely believed that the most beneficent practice was to let people work their way out of poverty, viewing economic hardship as a moral failing, and the allowance of such suffering as a thinning of the herd for the greater good. Yet, just as it is today, rising above economic limitations was not as easy a task as those with no economic limitations may have thought.

Order your copy of Money, Sex, Power & Faith today!